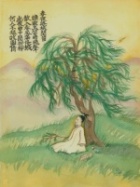

The Thing You Must Remember

By Maggie Anderson

The thing you must remember is how, as a child,

you worked hours in the art room, the teacher’s

hands over yours, molding the little clay dog.

You must remember how nothing mattered

but the imagined dog’s fur, the shape of his ears

and his paws. The gray clay felt dangerous,

your small hands were pressing what you couldn’t say

with your limited words. When the dog’s back

stiffened, then cracked into white shards

in the kiln, you learned how the beautiful

suffers from too much attention, how clumsy

a single vision can grow, and fragile

with trying too hard. The thing you must

remember is the art teacher’s capable

hands: large, rough and grainy,

over yours, holding on.

One of the few things I can thank standardized testing for is for introducing me to this poem.

Just a few years after I started teaching, it was one of the poems for the “Controlling Idea” essay of the ELA New York State Regents Examination, which is given to most eleventh graders in the state. It was the third of four essays in a two-day, six-hour, torturous exam. Thankfully for the students, the exam has been reconfigured recently.

The most remarkable thing is that even after reading and rating approximately one million (mostly competent if not completely inspired) essay responses on the poem, it still wasn’t ruined for me.

This is easily my favorite poem about teaching.

For many teachers, the start of the new school year means a welcome-back assembly where all sorts of fascinating information is imparted from those- in- the- know, like the importance of washing your hands for the precise duration it would take one to sing “happy birthday” and oodles and oodles of statistics regarding where your school scored last year in this and that, and where you must end up this year—or risk losing funding for art.

It’s part informative, part doomsday prophesying, and part pep-rally.

The recitation of sentimental poetry is a favorite at these events to help motivate teachers. It is usually some heartbreaking tale of a teacher who rescues some sad wretch of a smelly child from his horrific home life. Years later, the weary but dutiful teacher opens a letter from the formerly smelly child, and in it he credits her (and her alone!) with who the student is today, the scientist who cured all cancers. End Scene. Pass the tissues.

Did I mention that this poem is written in a forced ABABCDCD, etc. rhyme scheme with a sing-song rhythm? Well, of course it is.

But it isn’t the sentimental, poor poetry that’s the problem here.

The problem is that this is not really what teaching is about. Don’t get me wrong, it definitely happens that teachers save children from horrific things far too often. But let’s face it, the day-to-day life of a teacher is much less glamorous, much more routine, and comes with very little recognition for a job well done, and a whole ton of recognition for a job not-so-well-done.

So, this poem offers a refreshing look at the profession.

Notice how completely silent but poignant the teacher’s role is here. The speaker, a former art student, remembers exactly what (s)he wanted. She wanted to sculpt this damn dog that she could envision perfectly, and wouldn’t stop till she was happy with it.

Finally, after perfecting it, (but completely overworking the clay) the student puts the sculpture in the kiln.

What comes next is no surprise to the teacher.

The sculpture cracks in the kiln. If you want to be technical, the student fails. But doesn’t she learn not only about art, but also about life? Is this really a failure?

This lesson transcends the classroom and becomes authentically interdisciplinary. At least in retrospect, the student learns from this incident how in most any situation, being myopic can end up destroying your vision. She could have had a cool dog statue if only she could have seen it didn’t need to be the ONE way.

And really! How frustrating is it when people can only see things in one way?

I’m sure you know people who insist that they know the one “right” way to do something when in reality, the goal can be met in multiple ways.

Here’s one off the top of my head: there are many ways to fold a t-shirt. You might prefer one way better, but really, seriously, who cares about the details if it is in fact folded, put away, and not wrinkled when you pull it out to wear it.

Another thing I love about this poem: the teacher does not dive in to rescue the student at the last minute in some deus ex machina Greek Tragedy style. You don’t hear the teacher frantically repeating, “Umm, you know, Student, the more you overwork this clay, the more likely it is that it will be destroyed in the kiln.” “Umm, you know, Student, the more you overwork this clay, the more likely it is that it will be destroyed in the kiln.” She knows this is more effective.

For many reasons that I am not going to even try to start to discuss here, we are terrified of letting our students fail, even when they totally deserve and NEED to fail.

What a failure that is on us.

Yes, this teacher has a failing student in this lesson, but she is not remiss in her duty; she is not a bad teacher at all. In fact, she is a fabulous teacher. You better believe that next time, that student will not overwork the clay.

The lessons learned from failing are powerful. Please, take a minute and think about how failure has pushed you, motivated you, in your life. I guarantee that, no matter how successful you are, you have been pushed forward by your failures. Who would you be if you were never allowed to fail?

Who will our students be?

This teacher is not absent. She is not unfeeling of her student’s failure. Her hands are RIGHT there with her student’s the whole time. The teacher’s hands are what Maggie Anderson wants us to focus on. They are “the thing you must remember” from her title.

RIGHT there with her student’s the whole time. The teacher’s hands are what Maggie Anderson wants us to focus on. They are “the thing you must remember” from her title.

They are large, rough, and grainy, yes, but they are holding yours as you fail, ready to pull you up and have you try again.

In our most challenging times in life, if we are lucky, there are hands that cradle ours through our failures and push us to learn from them and try again. They don’t save us from failure, they guide us to success.

The art teacher in this poem, of course, can be a metaphor for any type of teacher— the meaning here can be expanded to include the type you have in school or out of school. It can be a parent or grandparent. It can be a friend.

But most likely, it will be an English teacher.